Fast Company: This platform wants to fix the disturbing lack of data on police violence

Only one in every 10 people who experience police violence report it. Raheem, which just formally launched in Oakland, enables anyone to easily report an interaction, and aims to collect new data to help drive reform

In 2007, Brandon Anderson lost the love of his life–a man he’d known since he was in third grade in Oklahoma City–to police violence. An officer had stopped him at a light in Oklahoma City and, after falsely accusing him of stealing a car, beat him to death. Anderson was working as an engineer and data analyst for the Army at the time; he had to keep his relationship a secret. When his partner was killed, he disclosed his sexuality and was discharged from the Army, and almost immediately set himself on a path toward using his data expertise to address the pernicious problem of police brutality that took his partner’s life.

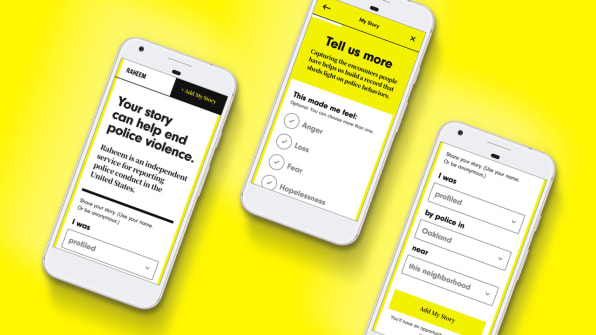

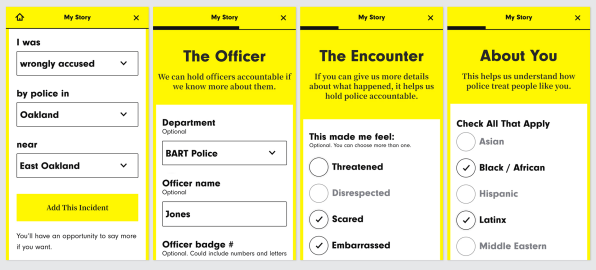

Over 10 years and a degree at Georgetown later, Anderson is now the founder of Raheem, an independent service for reporting police interactions. Raheem, which just formally launched in Oakland, California after a pilot run in San Francisco in 2017, allows anyone, following an interaction with the police, to record where it happened, the name of the officer, what transpired, and how they felt about it. The platform then uses data analysis to build a record of police behavior in a community–both for individual officers, and for the local district. Anderson was named a 2019 TED Fellow for his work, and during a talk introducing Raheem at TED in Vancouver, he said the data will help police oversight boards (independent bodies of residents assigned to assess and improve local policing) do their jobs, and will enable public defenders to challenge the credibility of violent officers in court.

In the U.S., police brutality is a known problem: all-too-numerous headlines in recent years have detailed the deaths of Philando Castile, Freddie Gray, and Mike Brown, among many others. But recent research suggests that police kill around three people per day in the U.S., and those people are disproportionately black men. Those findings, though, still fail to account for other violence and verbal and physical abuse people face at the hands of police.

That’s because the system for reporting police interactions, Anderson says, is fundamentally flawed. There are around 18,000 different police departments across the U.S. “Each has its own unique system for collecting and reporting police conduct,” he says. Most, however, require people who wish to report interactions to do so in person, during normal business hours, and within 90 days, which severely limits the number of people who report. In fact, an estimated nine out of 10 people who experience police violence don’t report it. And even if violence is reported, it’s up to the police departments to decide what they do with that information. Often, they do nothing. After Anderson’s partner was killed, he learned the officer who murdered him had a history of behaving violently at traffic stops, but had never been penalized for it.

Anderson initially launched Raheem as a chatbot through Facebook messenger, but shifted to the website and app-based model to streamline the reporting process. He’s been deliberate in coordinating the formal launch: He selected Oakland both because it’s where he lives and because of the city’s history of racial conflict, and he’s worked with community groups and legal aid clinic to get the word out about the platform.

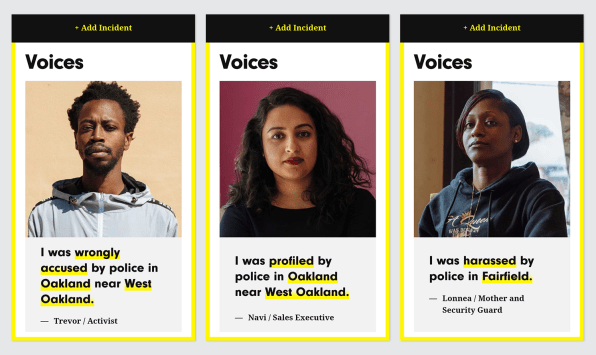

Through Raheem, which is Arabic for “second chance,” Anderson wants to empower communities to build up a record of how their police departments conduct themselves. On the site (and through a forthcoming app), residents can relay their experience–both good and bad–at any time, knowing that it will be incorporated into a growing body of data. Raheem also will build out a storytelling component to the site, which will feature the experiences of people abused by police to support the data with human voices.

While the launch in Oakland–and in more communities to come–is just getting started, the pilot in San Francisco proved promising. In the three months that the pilot ran, “we collected more data than the entire city collects in one year,” Anderson says.

Confluence Daily is the one place where everything comes together. The one-stop for daily news for women.